News

AWARDS & REVIEWS | VIDEOS | PRESS RELEASES

Taking “The Temp” to a New Level

By Norm Roby, Wine Review Online, November 12, 2024

The New Frontier for American Malbec

By Tamara Turner, Vintner Project, June 19, 2023

A Tale of Two Extremes': How changing climate impacts Oregon's wine industry

By Michaela Bourgeois and Emily Burris, Koin 6, February 16, 2023

Oregon Winegrowers glean lessons from last year's untimely frost

By George Plaven, Capital Press, February 15, 2023

Winter Slumber, The Importance of Winter to Viticulture and Wine Production

By Greg Jones, Oregon Wine Press, February 8, 2023

Top Vineyards, Leading Winemakers Help Albariño Grow In Northwest

By Eric Degerman, Great Northwest Wine, November 15, 2022

The 14 Best Malbecs for 2022

By VinePair Staff, VinePair, August 11, 2022

Despite Climate Change, Oregon’s ‘Other’ Grapes Are Thriving

By Julia Coney, VinePair, August 3, 2022

Talking with Wine Climatologist Gregory Jones

By Aaron Romano, Wine Spectator, April 22, 2022

VinePair; The 25 Best Rosé Wines of 2022

#22 Abacela 2021 Grenache Rosé, VinePair.com

Winemakers Are Poised to Lose Another Vital Tool to Climate Change

By Katheleen Willcox, Wine Enthusiast, February 15, 2022

CLIMATE CRISIS: Wildfires w/co-host Sonya Logan of Wine Titles, guests Drs. Greg Jones and Rebecca Harris

Apple Podcasts, January 31, 2022

While planning for GREEN WINE FUTURE 2022, our effects upon Terra continue. So while we build for GWF22, join host David Furer and producer Michael Wangbickler for their weekly podcast. Each 30 minute episode will focus upon a range of sustainability topics of concern to the wine world with expert co-hosts and guests in wineries, academia, and organizations.

Oregon wine: 2018 Abacela Tannat

Winerabble.com, January 20, 2022

"Southern Oregon is a sweet spot for this unique varietal! Tannat grapes have thick skins and high tannins but growers in Oregon have a knack for taming its wild personality. To soften the tannins, Abacela’s winemaker Andrew Wenzl used 86% neutral French oak and just 14% twice used barrels to age the wine. By doing so, he was able to integrate the tannic qualities into something really memorable and wonderful! Decant if you plan to open a bottle soon or buy several and age them through the next decade and beyond."

Greg Jones on KQEN's Morning Converstaion

December 30, 2021, listen to the full interview on KQEN:

SOU professor says climate change impacts wine-making

By Kevin Opsahl, Mail Tribune, December 27, 2021

Weather & Wine, CBS 60 Minutes, S54 E15 on December 26, 2021

Dr. Greg Jones, Climatologist, featured on story by Leslie Stahl. Watch the full segment here or here. Or read the transcript here or here.

Greg Jones appointed to Oregon Wine Board

Dr. Greg Jones was appointed to the Oregon Wine Board by Governor Brown for a three-year term. Greg Jones succeeds Hilda Jones after her two-term tenure on the Board. The Oregon Wine Board's President, Ted Danowski, commented in the December 2021 Grapevine, "We congratulate Tiquette Bramlett, Cristina Gonzales, and Dr. Greg Jones on their appointments by the Governor to three-year terms on the nine-member Oregon Wine Board. Your new Directors begin their service on Jan. 1, 2022. We thank outgoing Wine Board members Hilda Jones (six years), Bertony Faustin (three years), and Remy Drabkin for their insights, advice and energy as they step down and return to their businesses."

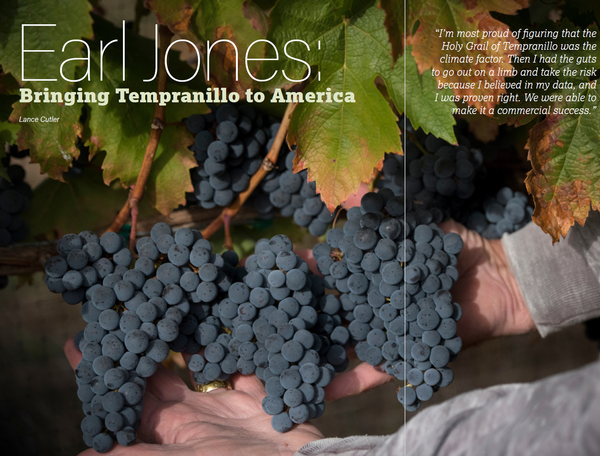

Earl Jones: Bringing Tempranillo to America

By Lance Cutler, Wine Business Monthly, November 2021

"Every now and then someone changes the way grapes are grown and the way wine is made; Earl and Hilda Jones did just that." - PDF of full article.

Oregon Wine, What We're Drinking; 2018 Abacela Grenache

By Michele Francisco, Winerabble.com, September 17, 2021

Greg Jones On The Future Of Southern Oregon Wine

By Joseph V Micallef, Forbes.com, September 9, 2021

Abacela Winery: Brings unique varietals to Oregon

By Craig Reed, Capital Press, September 9, 2021

The 25 Best Wineries in the United States

By Katy Spratte Joyce, Reader's Digest, August 10, 2021

Heat units in Northwest vineyards as much as 29% ahead of last year

By Eric Degerman, Great Northwest Wine, August 10, 2021

A focus on climate helps Abacela procude award-winning wine

By Craig Reed, The News Review, nrtoday.com, August 8, 2021

Abacela Names Greg Jones CEO

By Craid Reed, The News Review, nrtoday.com, August 8, 2021

Abacela winery names Gregory Jones as its new CEO

By Michael Alberty, OregonLive.com, July 23, 2021

Abacela winery in Roseburg has named former Linfield University director of wine studies Gregory V. Jones as its new CEO. Abacela’s owners, who also happen to be Jones’ parents, are pleased as punch. Read the full article.

Millenial Wine Competition: 6 Wines to pair with grilling

#5 Abacela 2020 Grenache Rose, Millenial Competition, June 29, 2021

Abacela: The Rise of Oregon Tempranillo

By Joe Campbel, The Vintner Project, June 8, 2021

Abacela announces a new partnership with Authentic Wine Selections

Roseburg, Oregon, May 26, 2021 – Abacela Vineyards & Winery, a Roseburg-based winery, announces a new wholesale distribution partnership with Authentic Wine Selections, an Oakland, CA-based fine wine distributor. Read the full Press Release.

Unique Wine Tasting Experiences

By Jen Anderson, Travel Oregon, April 28, 2021

Malbec: Southern Oregon's Rising Star

Oregon is famous for Pinot Noir, but US editor W. Blake Gray argues it has another strong suit, too.

By W. Blake Gray, wine-searcher.com, March 20, 2021

Abacela announces new partnership with Cru Selections

Roseburg, Oregon, March 2, 2021 – Abacela Vineyards & Winery, a Roseburg-based winery, announces a new wholesale distribution partnership with Cru Selections, a Woodinville, WA based fine wine distributor. Read the full Press Release.

Planet Grape Wine Reviews - Master Sommelier Catherine Fallis

2017 Fiesta Tempranillo, 94 points; Medium-bodied with ripe plum, cherry and floral notes; concentrated flavors with smooth velvety body and a long warm boysenberry finish - a true crowd pleaser.

2017 Malbec, 92 points; Rich and complex with earthy notes, black plum, mixed berries and chocolate; structured texture, well-balanced with juicy acidity.

2017 Fifty-Fifty (Tempranillo-Malbec), 91 points; Intriguing with focused blackberry, marionberry and nutty nuances, larger more structured texture and well-integrated spicy oak with a juicy cranberry finish.

Abacela 2017 Estate Fiesta Tempranillo

By Great Northwest Wine, January 13, 2021

Rated "Excellent" - In many regards, there are two wines released each year that serve as the Northwest’s emblematic expressions of Spain’s signature grapes Albariño and Tempranillo. Both hail from Abacela – the country’s commercial-scale launching pad for both varieties – and here’s the red example of the style reminiscent of the Ribera del Duero. Billed as fresh and fruity, Fiesta is the approachable ambassador of Tempranillo while offering lots of layers with gusto. Founding winemaker Earl Jones’s research with Clone 2 Tempranillo is seen as the key to this program. There’s an inkiness to the nose of elderberry and brambleberries, but also a spicy gaminess bringing pinches of cumin and sage. A deliciously massive entry of bold purple fruit gathers up some musculature on the midpalate that leads out with a nibble of Western serviceberry in the finish. Suggested pairings include chorizo, Manchego cheese and anything off the grill.

Top 20 Northwest Wines of 2020

By Eric Degerman, The Seattle Times, October 2020

No one in the Northwest matches Earl Jones’ devotion to Iberian Peninsula varieties, and this fortified dessert wine from Southern Oregon is dense, fruit-forward, fresh and complex with dark purple fruit, sweet herbs and nuttiness.

Region’s fortified wines provide sweet warmth on chilly nights

By Eric Degerman, HearldNet.com, October 20, 2020

"This past summer, 48 Northwest wineries submitted samples for Wine Press Northwest’s first large-scale judging of fortifieds since 2015. Abacela winemaker Andrew Wenzl earned four “Outstanding!” ratings for the Jones family, including the Abacela 2014 Estate Port, which topped the judging."

Triumph of Tempranillo; Abacela honors 25 years of leading an American-Spanish wine revolution

By Sophia McDonald, Wine Press Northwest, October 1, 2020

Twenty-five years ago, Dr. Earl Jones planted a dream in the Umpqua Valley. ...he applied his skills and tenacity as a researcher to a new quest: finding the best place in the United States to grow Tempranillo."

Abacela Winery 2019 Estate Grenache Rosé

By Great Northwest Wine, October 1, 2020

Rated "Outstanding!" - As much acclaim as the Jones family has merited for its work with Albariño, Tempranillo and Port programs, they’ve also earned five career Platinums from Wine Press Northwest magazine via its rosé. That success began with the 2008 vintage – Andrew Wenzl’s first as head winemaker. His latest example has qualified for the 2020 Platinum via gold medals at three West Coast competitions, and our panel would agree with those awards. The festive color waves you in for some fun and tickles the fancy by bringing hints of pink grapefruit, Rainier cherry, honeydew melon and strawberry/watermelon. Its structure is compelling, clean and refreshing with a raspberry finish that’s ideal for tapas. This fall, 25% of Abacela’s sales of this rosé, its Albariño and Syrah will be donated to the Greater Douglas County United Way for wildfire relief.

Abacela tops spirited tasting of Northwest port-style, fortified wines

By Eric Degerman, Wine Press Northwest, September 23, 2020

"Earl’s comment; "Abacela entered five port style wines and won 1st place (2014 Vintage Style Port) and three more highest ratings and one excellent rating. Thus 5 of 5 Ports rated excellent or better."

Nine All-American Grenache Rosés

Wine Enthusiast, August 12, 2020

"This is a powerful fruit-driven wine..." 2019 Grenache Rosé - 90 points. Editors’ Choice. —P.G.

Outside the Box - Loyal patrons react to “new normal”

By Paul Omundson, Oregon Wine Press, August 1, 2020

"Abacela, where owners Earl and Hilda Jones first introduced Tempranillo to Oregon, is in the midst of celebrating its 25th birthday..."

Cycling Series: Part 5, Umpqua Valley

By Dan Shryock, Oregon Wine Press, August 1, 2020

"Cycling the Umpqua Valley should include a visit to Abacela Winery..."

Bringing Tempranillo to Oregon - An interview with Earl Jones

By Liza B. Zimmerman, Forbes.com, July 22, 2020

"Trying to grow and bottle varietal Tempranillo, a wine that had never been successful in the U.S., was risky but science is a solid guide and today 25 years later everything we grow on our estate is site climate matched." -Earl Jones

Oregon Wine, What We're Drinking - 2015 Abacela Reserve Tempranillo

By Michele Francisco, Winerabble.com, July 10, 2020

"Wow, this wine is complex! ...It’s built for aging, so don’t hesitate to lay a bottle or two in your cellar to enjoy in the next decade."

Wine, etc.; Tempranillo In Oregon

By Tom Marquardt and Patrick Darr, Capital Gazette, June 24, 2020

Comparing Wines Made From Tempranillo Grapes

By MoreAboutWine.com, SouthFloridaReporter.com, June 21, 2020

"Tempranillo in Oregon too... We’re suckers for a good story"

Wines to Know; Abacela 2019 Grenache Rosé

By Karen MacNeil, winespeed.com, June 5, 2020

"...we liked this Abacela from southern Oregon for going up against some pricier, fancier competitors–and still tasting the best!"

Oregon Wine, What We're Drinking - 2015 Abacela Reserve South Face Block Syrah

By Michele Francisco, Winerabble.com, May 30, 2020

Oregon Wine, What We're Drinking - 2017 Abacela Tempranillo Fiesta

By Michele Francisco, Winerabble.com, May 24, 2020

The Innovative and Delightful Wines of Abacela

By Frederick Thurber, SouthCoastToday.com, May 22, 2020

"These wine are really exceptional; I don’t think I have ever tried a winery’s lineup that was this perfect, from top to bottom."

Great Northwest Wine: Reach for rosé at any time, anywhere

By Eric Degerman of Great Northwest Wine, The Spokesman Review, May 2020

Tempranillo For Two In The Umpqua Valley

By Margarett Waterbury for Travel Oregon, May 2020

After an early-morning departure from Portland, our first stop is Abacela, Oregon’s tempranillo pioneer, with the hope that founders Earl and Hilda Jones can help shed some light on how and why tempranillo first took off in the Umpqua. By Margarett Waterbuy

Oregon Wine, What We Are Drinking - 2019 Albarino

Winerabble.com, May 2020

If you have a hankering for the tropics, you must buy this wine! If I had only one word to describe the Abacela Albariño, it would be passionfruit! Thankfully, I’m not limited to just one word, but wow, this wine brings me right back to Hawaii!

Abacela Vineyards in Umpqua Valley, Oregon: A “Special Pocket of the World” Where Spanish Varieties Flourish

Grape Experiences, April 25, 2020

"What I discovered during our conversation was that Earl Jones, forthcoming and friendly, intelligent and innovative, is an undeniable force in the wine industry."

Drinking With Esther - Abacela Tinta Amarela Umpqua Valley 2016

SFChrinicle.com, April 17, 2020

This southern Oregon winery has been a leading producer of Spanish- and Portuguese-style wines for decades, and it continues to make solid renditions of Tempranillo, Graciano and Albariño, among other wines. But I was particularly excited to try this Tinta Amarela, a Portuguese grape variety that Abacela owners Earl and Hilda Jones believe they were the first in the U.S. to bottle as a varietal wine. I’m sure I’ve had Portuguese red blends, including Ports, that have included Tinta Amarela before, but I’d never tasted it on its own. Abacela’s version is densely structured, with forest berries, graphite and cocoa powder flavors.

Abacela appoints Gavin Joll to General Manager

WineBusiness.com, April 2020

Abacela is pleased to announce that Gavin Joll will start as General Manager May 1st, 2020. Gavin, a native Oregonian and graduate of Willamette University, has worked in the wine industry since 2004, including thirteen years as the General Manager of White Rose Estate in the Dundee Hills.

Oregon Wine, What We Are Drinking - 2019 Grenache Rose

Winerabble.com, April 2020

Abacela, located in Oregon’s Umpqua Valley, is celebrating 25 years of winemaking! Owners Earl and Hilda Jones traveled all over the world, searching for a prime location in which to grow Tempranillo, finally landing in Roseburg. This rosé is made using Grenache fruit from their estate vineyard.

Why Wine? An Interview with Earl Jones of Abacela Winery

By Michelle Francisco, Winerabble.com, March 2020

Look at homegrown products to avoid tariff woes on imports

By John McDonald, Cape Gazette, January 20, 2020

"Umpqua Valley near Roseburg. Here I like Abacela. They live outside the Oregon box and produce wine normally associated with Portugal and Spain: Tempranillo, Albarino, Dolcetto, Tinto Amarela, Graciano, an excellent Malbec and Port. All are grown in small, defined lots on the slopes of a cone-shaped foothill for maximum terroir effect. Clever viticulture. Barbara and I visited in 2016. Their vineyards and buildings were very carefully groomed. Always a good omen. Their Barrel Select Malbec rated 91 McD, 2011-15 around $30/bottle. Abacela also does a good job with big bottles for those who like unique."

Cheers to these 2 Roseburg wineries: Gerry Frank's picks

By Gerry Franks, The Oregonian, July 14, 2019

"When Earl Jones and his wife, Hilda, adopted Oregon as their home in the early 1990s, Oregon’s small wine industry had already earned an international reputation for great pinot noir. But the Joneses had come to do something different."

Great Wines for 2020, Part II

By Lou Phillips, Tahoe Weekly January 21, 2020

"Abacela Vineyards and Winery in Roseburg is a thought and action leader here with multiple, different wines each vintage, the majority of which are out of the box and, more importantly, delicious. It also farms some of the steepest vineyard terrain anywhere; one vineyard is Chaotic Ridge Parcel, which along with climate and soils, translates into real terroir in the bottle." Read full article

The Nittany Epicurean Review

By Michael Chelus, Read full article

"We're headed back to Abacela to enjoy a red wine that really blew me away."

Oregon’s Iberian Connection

By Paul Gregutt, Wine Enthusiast Read full article

"Tempranillo is the leader here. Its introduction signaled the start of a spreading Iberian influence initiated by the Abacela winery more than two decades ago."

Wine Enthusiast's Top 100 Wines of 2018

Abacela's 2015 Fiesta Tempranillo on the Top 100 Wine of 2018 list by Wine Enthusiast!

10 Top Wines To Serve To Your Next Dinner Guests

Abacela's 2017 Albarino listed in Forbes.com's 10 Top Wines!

Abacela Appoints Paula Caudill to National Sales Manager

We are pleased to announce that Paula Caudill is being promoted to Abacela’s National Sales Manager effective November 1, 2018. Many of you have come to know Paula through the years via emails, phone calls, and in person at the winery. She has been and will continue to be a great asset for Abacela since 2002. Paula replaces Sarah Waring who will be leaving Abacela after 3+ years of outstanding leadership building the Abacela brand on a national level. We wish both Sarah and Paula the best in thier new adventures.

Does Southern Oregon Need (or Want) a Signature Grape?

By Paul Gregutt, Wine Enthusiast, October 24, 2017

“Currently, the best option for Southern Oregon is Tempranillo. In Spain—especially the Rioja and Ribera del Duero regions—Tempranillo produces exceptional, expressive wines. Yet, unlike the Rhône grapes that have proliferated in the western U.S., Tempranillo remains almost invisible as a varietal wine.” PDF

Oregon Wine Press - Cellar Selects; "Blanc? Check!"

2016 Albariño, A cornucopia of fruit. Peach dominates the aroma followed by pear and jasmine. A slight, pleasantly perfumed bitterness leads to lime, dragon fruit, nectarine, tangerine and apricot flavors, ending with a fleshier, fruitier finish.

Wine Business Monthly

Varietal Focus: Tempranillo

Earl and Hilda Jones.... "They planted their first grapes in Southern Oregon in 1995; and after 22 years, they are one of the foremost producers of Tempranillo in the New World." Read the full PDF.

The Changeup: Goodness Graciano - A trip to Spain with a sip from Southern Oregon

By Michael Alberty Oregon Wine Press

A decade ago, when traveling to Spain to explore as many wine regions as possible, I toured from the desert sands in Jumilla to the lush green hillsides of Galicia. Consequently, I developed quite a passion for Spanish wine and food culture, which is why my curiosity was piqued when I learned a winery in Oregon was making wine with Graciano, one of the rarest red winegrapes in Spain. It was no surprise to discover the winery was Abacela, where founder Earl Jones and his head winemaker, Andrew Wenzl, craft some of the finest examples of Tempranillo and Albariño in the New World. I couldn't drive to Roseburg fast enough. more

SIP Northwest Magazine; Just Desserts, Sweet Wines of the Pacific Northwest

Strength in Numbers: Fortified Bottlings

Abacela Winery in Southern Oregon's Umpqua Valley produces two dessert wines in this traditional style with Portuguese grapes. Earl Jones, owner of Abacela, says the sloping hillside microclimates of his valley are quite similar to that of western Portugal's main dessert wine region, the Douro Valley, where Port is produced. For that reason, he grows classic Portuguese varieties like Tinta Roriz, Tinta Amarela, Bastardo, Tinta Cão and Touriga Naçional; five of the over 30 varieties allowed in Port production. - Sipping Sweets 2013 Estate Port, This beautiful wine is inky dark in the glass with aromas of black cherry, dark plum, brambleberry, dates, savory spices and dark chocolate.

Great Northwest Wine Review

Outstanding!, Vintner's Blend #16

"The robust Spanish grape Tempranillo is the historic headliner at storied Abacela in Southern Oregon, and so it understandably makes up essentially half of this Mediterranean-style blend that calls upon 11 varieties. Syrah is the next grape up (21%) for winemaker Andrew Wenzl, who used it to create remarkable balance while toning down the tannins. There’s still ample grip, yet there’s an abundance of fruitiness to match. The nose features hints of black currant, cherry and lingonberry with touches of caramel corn and oregano. Inside, blackberry jam and bittersweet chocolate flavors are joined by tannins reminiscent of espresso grounds, which are led out by a raspberry cream finish." 3/14/2017

Wine Enthusiast Reviews

Paul Gregutt, Wine Enthusiast, April 2017

91 points, 2014 Fiesta Tempranillo

"Fiesta is the lightest, most fruit forward of the four different Tempranillos from Abacela. In a great year such as this, it's also substantial and authoritative, with deeply driven flavors of red and blueberry fruit, a whiff of oak and slightly grainy tannins. This wine clearly over-delivers for the price."

90 points, 2014 Barrel Select Graciano

"Rare in Oregon (or anywhere this side of the Atlantic), this Graciano pushes a mix of pomegranate, cranberry and raspberry fruit front and center. It dips in the midpalate, then re-gathers with a mix of tea, coffee grounds and dark chocolate wrapping up the finish. Put this ringer into your next tasting of Spanish wines and you'll stump everyone."

90 points & Editors' Choice, Vintner's Blend #16

"Roughly half estate-grown Tempranillo, this smooth and deeply-fruited red includes small amounts of 10 other grapes. For all that it's complete, complex and composed, with pomegranate jam, loganberries, polished tannins and prolonged power. Drink now through 2020."

Top 12 NW Tempranillos

Portrait Magazine

Oregon Business Magazine names Abacela in "100 Best Fan-Favorite Destinations in Oregon"

December 2016

Promise fulfilled at the First Oregon Tempranillo Conference

By Randy Caparoso, The Tasting Panel, June 2016

Abacela Featured in the Wine Spectator

Syrah Stars in Southern Oregon, By Harvey Steiman, June 15, 2016

Back to Oregon for some outstanding wines

By John McDonald | May 16, 2016 Cape Gazette

Great Northwest Wine Review

Outstanding!, 2013 Fiesta Tempranillo, Great Northwest Wine

"The Northwest Tempranillo master has proved his expertise once again. Earl Jones' Abacela estate grapes from 2013, put into the capable hands of winemaker Andrew Wenzl, were used in this fruit-forward wine aptly called Fiesta. And you'll want to start a celebration of your own after sampling it. Its nose opens with mint, spicy oak and nimble cherries. In the mouth, the cherries are dark, dipping down toward dark Marionberry skin, then unearthing Abacela estate's minerality and grippy tannins. It’s a huge mouthful – “Yuuuge, I tell you” – that calls out for a rare ribeye amply dusted with cracked black pepper. This earned a double gold medal at the 2016 Cascadia Wine Competition."

Abacela, Bunnell stand out at Pacific Rim International Wine Competition

Best of Class & Gold Medal 2015 Grenache Rosé

SAN BERNARDINO, Calif. – Abacela in Southern Oregon and Bunnell Family Cellar in Washington's Yakima Valley each were awarded three gold medals Thursday at the 31st annual Pacific Rim International Wine Competition in Southern California. Eight wines from the Pacific Northwest captured best of class honors at the two-day fundraiser for the National Orange Show. One of those BOC awards went to Abacela winemaker Andrew Wenzl for the latest vintage of his perennially popular Estate Grenache Rosé made from the Fault Line Vineyards of Earl and Hilda Jones. Two other wines from the 2015 vintage – Albariño and Muscat – also went gold.

Great whites from 2016 Cascadia Wine Competition

Gold 2015 Muscat: Annually, Abacela crafts one of the most beautiful and graceful Muscats in the Pacific Northwest. This new vintage is no exception, thanks to aromas of rosewater, lavender and clove. On the palate, it offers flavors of lychee, pink grapefruit and Golden Delicious apple. Its 3% residual sugar and gentle acidity make this a delicious and approachable sipper.

Gold medal reds from 2016 Cascadia Wine Competition

Double Gold, 2013 Fiesta Tempranillo

The Northwest Tempranillo master has proved his expertise once again. Earl Jones’ Abacela estate grapes from 2013, put into the capable hands of winemaker Andrew Wenzl, were used in this fruit-forward wine aptly called Fiesta. And you'll want to start a celebration of your own after sampling it. Its nose opens with mint, spicy oak and nimble cherries. In the mouth, the cherries are dark, dipping down toward dark Marionberry skin, then unearthing Abacela estate’s minerality and grippy tannins. It’s a huge mouthful – “Yuuuge, I tell you” – that calls out for a rare ribeye amply dusted with cracked black pepper.

Top wines from 2016 Cascadia Wine Competition

Best Dessert/Gold 2015 Blanco Dulce: Southern Oregon winemaker Andrew Wenzl crafted a beauty of a dessert wine here, using estate Albariño that hung on the vines and accumulated sweetness well past its normal harvest time. Aromas of honey-glazed apricot and intense Christmas spices lead to flavors of candied orange peel, poached peach and vanilla ice cream. It is a stunning dessert wine. Read more.

Abacela awarded People's Choice at Greatest of the Grape Wine Gala

Best Wine 2012 Northwest Block Reserve Malbec and Best Wine & Food Pairing with K-Bar Steakhouse. Read more.

Abacela earns four 90+ point reviews from Wine Enthusiast

93 Points & Cellar Selection, 2012 Northwest Block Reserve Malbec; 92 Points & Editors’ Choice, 2012 Barrel Select Syrah; 91 Points & Editors’ Choice, 2013 Barrel Select Malbec; 90 Points, 2013 Barrel Select Tinta Amarela; WineMag.com. April 2016 Issue

Get to Know a New Side of Tempranillo

Tempranillo Bottles to Try. By Rachel Singer, Eater.com. February 2016

Terroirist.com: American Tempranillo

92 points, 2012 Abacela Tempranillo Barrel Select Estate. Read the full article on Terroirist.com. February 2016

A little bit of Spain taking root in Oregon

Lovers of the Spanish wine varietal called Tempranillo can take heart that this grape is taking root in the soils of Oregon. By Victor Panichkul, Statesmen Journal. February 2016

Southern Oregon wines' gaining clout could bring onslaught of tourists

The winsome wines of Southern Oregon are gathering acclaim far beyond the Cascades and Siskiyous. Read the full article. January 2016

Southern Oregon named 10 Best Wine Travel Destinations

Abacela is mentioned as a must-see winery in Roseburg. Read the full Wine Enthusiast article. January 2016

Northwest Tempranillo continues to shine

Abacela's 2013 Fiesta Tempranillo and 2012 Barrel Select Tempranillo highlighted by Great Northwest Wine. January 3, 2016

Abacela makes Top 100 Wines of 2015 list

Our 2012 Fiesta Tempranillo made Great Northwest Wine's "Top 100 Wines" of 2015 list!

140 year old vines discovered at Abacela

Abacela discovers 140-year-old Mission grape planting on estate. Read the article. November 26, 2015

Abacela Releases #UmpquaStrong Wine to support the UCC Relief Fund.

Abacela proudly presented Ellen Brown, of the Umpqua Community College Foundation, with a check for more than $18,000. The money was raised by the spontaneous generosity of our bottle, glass, cork, label and capsule suppliers and the Abacela staff and owners for the bottling of #UmpquaStrong. 100% of the proceeds of this bottling went to the #UCCReliefFund (Umpqua Community College). The wine sold out in less than 48 hours, but you can still donate at Greater Douglas United Way.

Statesman Journal; Oregon wines for Christmas dinner

Abacela's 2012 Barrel Select Syrah was chosen by the Statesman Journal as a top wine to have with your Christmas roast.

Portland Monthly; Oregon's 25 Best Wines Under $25

Abacela's 2014 Albariño was chosen by Portland Monthly Magazine as one of Oregon's 25 Best Wines Under $25. Read the article. September 21, 2015

Earl Jones celebrates more history at Abacela

Great Northwest Wine by Eric Degerman on May 27, 2015. Read the article.

8 Excellent Oregon Varieties That Aren't Pinot Noir

Northwest Spain and Portugal's native grape, Albariño, in Oregon results in a fruitier wine than a typical Rías Baixas version. The best examples also show appealing minerality and crisp, ultra fresh flavors of celery, jícama, cucumber and a dash of daikon radish. Abacela, the Umpqua winery that pioneered Tempranillo in Oregon, has perfect Albariño, keeping alcohol levels low and acidity high. Read the full Wine Enthusiast article.

2015 American Winery of the Year Nomination

Abacela is one of five wineries nominated by the Wine Enthusiast for their Wine Star Awards "2015 American Winery of the Year". Read the article.

Northwest Wines: A few 2014 Northwest rosés to tuck in your fridge

Our 2014 Grenache Rosé is featured in The Bellingham Herald.

1859 Magazine

The Beauty of the Blend; Oregon's red blends come together to produce a tapestry of flavors that will improve your dining experience. Our Vintner's Blend #14 is highlighted.

Lifetime Achievement Award

Earl and Hilda Jones were awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Oregon Wine Board at this year's Oregon Wine Symposium. Read the press release.

Greatest of the Grape

Our 2012 Malbec wins a Gold Medal from the professional judging and runner-up Best Wine & Food Pairing.

NWwines.com

Wine of the Week for February 7, 2015, 2011 Dolcetto

Oregon Wine Press

"Value Pick" February 2015, 2011 Dolcetto and 2011 Malbec

Chicago Tribune

2013 Albariño featured in the article Offbeat grapes making their way in American vineyards

Umpqua Valley: Only Hours From Napa, but a World Away

By Rachel Levin, The New York Times, July 6, 2014

Statesman Journal

Wine: Try rosés from Oregon: 2013 Grenache Rosé

Sip Northwest Magazine

"Daily Sip" by Erin James 2013 Albariño

SFGate.com

2013 Grenache Rosé is a "Heavy Hitter" by Jon Bonné.

Oregon Wine Press

"Value Pick" July 2014, 2013 Grenache Rosé

Oregon Wine Press

"Value Pick" June 2014, 2013 Viognier

Great Northwest Wine

#14 of "Top 100 Wines", 2012 Albariño

James Melendez, JamesTheWineGuy.com

Top 100 Wines of 2013, 2009 Estate Tempranillo

The Passionate Foodie

"2013: Top Wines Over $50", 2005 Paramour

Examiner.com

"Southern Oregon Wine of the Week" 2012 Albariño

SFGate.com

"Top 100 Wines of 2013" 2012 Albariño

The Seattle Times

"Top 50 Regional Wines" 2012 Albariño

CNN Money

Taking risks in retirement, October 2011

Wine Business

"Abacela Syrah is Southern Oregon's First 95-Point Wine" March 09, 2009 Read the Article Here

"In an historical perspective, 95-point wines are rare. An online examination of data from wines reviewed in the Wine Enthusiast and Wine Spectator revealed that together these two highly respected magazines have tasted approximately 10,000 Oregon wines of which they rated only 20 wines from just 12 Oregon wineries at 95 points or higher. None of the fruit for these wines was sourced, nor were any of the producing wineries located south of Oregon's famed Willamette Valley, known for world-class pinot noir"

How climate change affects Oregon wine

OPB, Think Out Loud, By Elizabeth Castillo, April 25, 2022

As new weather patterns linked to climate change emerge, what does that mean for Oregon’s wine industry? We check in with Greg Jones, a wine climatologist and the CEO of Abacela Vineyards & Winery in Roseburg.

Note: The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: From the Gert Boyle studio at OPB, this is Think Out Loud, I’m Dave Miller. About 30 years ago, Greg Jones got a PhD, and soon began a career in wine climatology. At about the same time, his family was starting the Abacela Winery in the Umpqua Valley. Jones spent years studying and teaching wine climatology. Last year, after his father retired, Jones stepped in to become the CEO of Abacela. He joins us now to talk about climate change, and the future of winemaking in Oregon and around the world. Greg Jones, welcome.

Greg Jones: Thank you very much. Good to be with you today.

Miller: Oregon has some real variation in its climatic zones. Just to take two examples, the Willamette Valley is pretty different from southern Oregon. So let’s take these two places one by one in terms of what you’ve seen over the last three decades in terms of climatic changes, first in the Umpqua Valley.

Jones: Well, if you look at trends and temperatures, you know, the whole entire state has warmed over the past 3 to 4 or 5 decades. The warming has been roughly about the same, although it’s a little bit more in some of the eastern areas of our state than it is in the south and the west, but overall the temperatures have trended roughly about the same in the state. If you look at the region here in the Umpqua Valley, we’ve warmed upwards of 1.5 to 2°F in that period of time.

In terms of precipitation, we haven’t seen dramatic changes. The Western United States is just prone to summer droughts, and sometimes those summer droughts extend themselves into the winter. We’ve been in a relatively dry period right now, but the overall trends in precipitation are not quite as evident as those in temperature.

Miller: What have the changes that you have seen in temperature, and whatever changes there have been in terms of precipitation as well going back a number of decades, what have those meant in terms of the qualities of the fruit you get on any particular vine?

Jones: Well, I mean, I think if we’re talking about Oregon, I think it’s really good to go back to, let’s say the 1950s, when there really were no people growing wine grapes in the state for commercial production. And that was largely because our climates were just not conducive, they were quite cold, growing seasons were shorter, a little bit more rainfall in the wrong period of time. And it was a challenging place to grow grapes in the 1950s.

The early pioneers that started in the 60s, you gotta give them just a tremendous amount of credit for wanting to come and do something that they thought was very feasible. But they did it in a challenging climate. But boy, you fast forward to where we are today, and those pioneers, you’ve got to really look at them and say, boy, they were right that we’re in a place today where our climate is very suitable to growing grapes. It’s a little bit different in the Willamette Valley, which is a little bit cooler and wetter than parts of southern Oregon or eastern Oregon. But in general, the entire state has become more suitable since the 1960s, when we first started.

Miller: Is the Willamette Valley of 2022 more like Burgundy of 1970?

Jones: No actually, the Willamette Valley today is very similar to Burgundy of today. And I think what’s happened in Burgundy is that Burgundy was always a little bit more suitable than the Willamette Valley, but today they’re more similar overall. Burgundy and the Willamette Valley are best known for pinot noir, and both of them are kind of in the sweet spot for that variety in terms of the types of temperatures and growing season that they like.

Miller: To go back to this question about the fruit, has it changed? And I know obviously we’re talking about a bunch of different microclimates and different hills facing more southerly or more easterly or whatever, so maybe it’s hard to make super broad generalizations. But have the grapes responded to warmer seasons?

Jones: Sure. I mean, there’s quite a few different ways of looking at this. But in general, number one, the plant system, the grapevine itself has shown us over time worldwide, in every wine grape region that I’ve done research, including Oregon, the grapevine is going through its growth cycles a little bit earlier, whether it be bud break or flowering or the changing of color, or even harvesting. The grapevine is telling us that climates have trended.

In terms of fruit, what we typically look for in the industry is we’re looking for grapes to ripen to ideal characteristics to make a high quality wine. And in doing so, there’s really four things that are happening. I call them ripeness clocks, and the ripeness of sugar of course is number one, but there’s also acid, and then there’s also flavors/aromas that tend to come into play, and then phenolics that happen. And so all of those things are happening simultaneously in the grape. But in a warmer climate, sugar ripeness has a tendency to accelerate. So you get more sugar quicker within the fruit. At the same time, you tend to metabolize or respire acids. And so in a warmer climate, and we’ve seen this, there’s a lot of research out there in the world that has shown this, we’re more sugar rich earlier than we’ve been historically. And that has a balancing effect on issues of acid and flavors and phenolics.

Miller: So it would be up to a winemaker to recognize that and to plan for it or correct for it?

Jones: Sure, sure. And you’re very right, I think that the one thing that we’ve seen over time that’s been pretty clear from records is that more sugar equals a little bit more alcohol. We’ve definitely seen trends in alcohol going up. But some of that could be due to wine writers, and how they tend to like a bigger bolder wine today than in the past. But you’re right, a winemaker’s key is to work with the vineyard grower to make sure that the fruit gets to them and the kind of characteristics that they’re looking for. But then the winemaker is the one who massages that, and applies essentially their art to the product.

Miller: So as you noted, it seems like if I understand you correctly, things have gotten even better over the last five decades in the Willamette Valley for growing pinot noir. But we also understand that climate change is accelerating, and things are going to get even hotter and even more extreme in various ways, there will be more extremes at various times, whether that means temperature related or precipitation. Based on the direction we’re going, is the Willamette Valley going to remain ideal for pinot noir?

Jones: This is largely what I’ve been studying for 25 plus years now, is trying to better understand what the thresholds are for optimum conditions for any given variety, pinot noir or chardonnay, or cabernet sauvignon, whatever it may be. Of course pinot noir is much more of a cooler climate variety. But we know that it has what I call a climate niche of roughly about 4°F within the growing season, from the coolest places to the warmest places doing it. So if we consider where the Willamette Valley is today, back in the 60s and 70s, we were on the cooler limits of pinot noir suitability. Today we’re centered within that suitability. So a few degrees of warming has put us into a much more goldilocks, for lack of a better term, framework. We’re the sweet spot, so to speak.

However, if we continue warming, since 1980 the trend has been almost linear, and if we continue warming at that rate, we will at some point in time pass what we know to be the threshold for really warm conditions for pinot noir. Now, that doesn’t say that there can’t be some form of adaptation, whether it be in the vineyard or in the winery, to kind of massage that a little bit or make it a little bit more elastic over time. But the issue is that given what we know about pinot noir today, another 20, 30, 40 years of warming could mean that pinot noir is questionable in some places in the Willamette Valley, and maybe even more suitable than others.

Miller: Like maybe British Columbia or something?

Jones: Exactly. If you look at the framework behind all of this globally, what we’ve basically seen as we’ve seen is a warming that has produced latitudinal shifts toward the poles in both hemispheres, a shift toward the coastal zones, and then also a shift toward higher elevations. And so if there is more elevated areas to plant, then there is the potential to mitigate those kind of changes in climate.

Miller: What does that mean in terms of the bottom line in marketing, if in general wine drinkers around the world associate, say, Burgundy and the Willamette Valley with pinot noir, but if decades from now those grapes don’t really want to be there?

Jones: I do think that there’s this kind of this push/pull between the production system and the consumer system in terms of thinking about this. And I think in Europe, part of the challenge there is that they have hardwired these legal frameworks behind what varieties can grow in what regions. And so in Europe, the ability to adapt and change maybe to a new variety, a new style, is quite a bit more challenging than we see in new world in viticulture. So, if we warm and need to think about changing the way we grow the grapes of the varieties that we grow, we don’t have the same policy or legal framework that they do in Europe.

But then getting back to the consumer question that you had, I think as consumers, we also need to be very aware of this puzzle. There’s a little bit of this idea that we all think that everything will always be the same, whether it be a cheese or a coffee or a chocolate or whatever it may be. But in a changing climate, we should never expect things to always be the same. And that’s why I think consumers, and myself included, we need to be aware of these kind of changes, and embrace what changes that the producers will put together within whatever agribusiness it is, and embrace those changes. And I think there is of course going to be a marketing challenge and a timing challenge with all of this, but it’s not going to happen overnight or within a year or two. It’s a longer term kind of framework that I think has both producer and consumer awareness being at the heart of it.

Miller: We just have a minute left. But what’s a varietal that you think could be one of the grapes of the future in the Willamette Valley?

Jones: Well, I think people are already playing around a little bit with different varieties. At least for red grapes, you’re hearing more people planting gamay noir. There’s a few people planting syrah, a few people planting tempranillo. So there’s other varieties that people are working with, and that’s an example of a changing climate, where growers are seeing that potential, and they’re seeing how well those varieties can do today. So I think that all of those have a very interesting place in the future.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.

Talking with Wine Climatologist Gregory Jones

By Aaron Romano, Wine Spectator, April 22, 2022

Greg Jones is the CEO of Abacela, the vineyard and winery his parents, Earl and Hilda Jones, founded in Southern Oregon’s Umpqua Valley in 1995. After earning a Ph.D. in environmental sciences from the University of Virginia and doing his dissertation on viticulture in Bordeaux, he has become a globally renowned atmospheric scientist and wine climatologist, sharing his knowledge with the wine industry in roles such as professor at Southern Oregon University and director of the Center for Wine Education Linfield College in McMinnville, Ore.

Jones’ research linking weather and climate with grapevine growth, fruit chemistry and wine characteristics has made him a popular speaker at wine-industry conferences and a prolific contributor to journals, books and reports, including to the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize–winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. He recently spoke with associate editor Aaron Romano about his career, how changing conditions benefit and challenge the wine industry, how wineries are adapting and what the future holds.

Wine Spectator: When did your interest in wine begin?

Greg Jones: I started cooking in high school. By the time I was at the end of high school, I had become a chef at a restaurant in the Bay Area. I remember one of my first jobs in Sausalito, I wasn't even old enough to drink, but they let me come in and listen and talk to the distributors selling wines.

WS: What came first, an interest in science or wine? And how did the two intersect into wine climatology?

GJ: I originally wanted to be a hydrologist, but climatology and meteorology piqued my interest. So I was in the right field [environmental sciences], to begin with; it just took me moving through that to really see the wine and climate science connections.

One of my advisors wanted me to study broadacre crops, like rice or corn or soybeans or wheat. I knew a little bit about the wine industry, and I knew that it provided a much more interesting background as a crop to study. I convinced him to allow me to study viticulture and wine production. All this happened right about the time my father was moving into growing grapes and making wine, and this parallel thing started happening.

I did my Ph.D. research in Bordeaux. At that time, during the mid-’90s, I probably had more data on Bordeaux grapegrowing and winemaking and climate and weather and soil factors than anybody at that point in time. That really expanded my thoughts around climate science in viticulture and wine production.

WS: What does a wine climatologist do?

GJ: Collecting data and understanding the patterns, structure and trends within that data is what a wine climatologist does. When I started this whole process, nobody in climate science studied viticulture and wine production. I was one of one.

I’ve installed dozens and dozens of weather stations and monitors all over the world. My family’s vineyard is probably one of the most instrumented vineyards you’ll find, including three full weather stations, 24 temperature sensors and 40 soil moisture sensors on 80 acres of vineyards.

I’ve spent a lot of my career attempting to understand better what makes certain varieties suitable to certain climates in terms of their productivity and quality. And in doing that, you know, you have to collect data. I’ve been doing quite a bit of fieldwork here in Oregon and a few other places. My datasets from Bordeaux, for example, were anywhere from 50 to 100 years long. Then you have to manage that data, manipulate and analyze the data, and interpret what it’s telling you.

WS: What are some misperceptions associated with climate and wine?

GJ: That latitude is an analog for the climate. If you looked at trying to take multiple climate factors and do an analog for them, Bordeaux’s most closely matched climate in the United States is in southern New Jersey. When you go to Bordeaux, you sweat during the summer because they have a lot of humidity in the air. In Napa, there is no humidity in the summer. Bordeaux gets 60 percent of its rainfall during the growing season. Napa gets 15. A big difference there.

WS: What are you seeing happening in the wine industry around climate impact on grape growing?

GJ: It helps to go back to when I first started as a student in the late ’80s and early ’90s. The vast majority of geoscientists worldwide were on the fence about what kind of trends were happening and how much influence humans had. … When I started collecting my data in Bordeaux, I found that the models I was trying to build on grapevine growth and productivity couldn’t work unless I included a trend. What that told me is that, even back then, climates were changing, and we weren’t really paying enough attention to it.

I remember giving a talk in 1995 or 1996 in Bordeaux; people there thought I was crazy. But I showed them what the data was saying: You’re in a trending environment, and temperatures are getting warmer. If all of our models at that time are correct, in the next 20, 30 years, you’re going to be in a very different place. And boom, fast forward: Here we are.

The impacts are varied. It depends on the region and the varieties being grown. It also depends on where the region was 30, 40, 50, 60 years ago and where it is today. For example, the Oregon wine industry did not exist in the 1950s. The biggest reason it didn’t exist is that the climate was not conducive to it. It was just too cold. Its growing seasons were too short and inconsistent, and it just would have been economically not feasible. Fast forward to where we are today. In terms of its recognition, Oregon today is a completely different place, and that kind of change has allowed our industry to really grow and be as recognized as it is.

We’re now talking about what the next 40 or 50 years may bring. Let’s do a what-if and say temperatures keep going up in a linear structure. Places like the Willamette Valley will be arguably somewhere between 2.5 and 4.5 degrees [Farenheit] warmer than they are today. The reason that that’s important is Pinot Noir only has a roughly 4-degree growing season climate niche worldwide. So, if we warm in the Willamette Valley by 3 or 4 degrees, we’re warming more than the entire known geographic climate spread of Pinot Noir today.

WS: Are there any particular regions that are most susceptible?

GJ: One hundred years ago, Burgundy made a much more elegant, lower-alcohol, lighter-color wine. Today it’s still Pinot Noir but has moved up the ladder, so to speak, from cool-climate limits to the warmer-climate limits. It’s not that it’s at its limit, but it makes a different style, even though the typicity is still Pinot Noir.

If you don’t get the climate right, you can’t grow Pinot Noir. But, on the other hand, suppose you’re in a region where the main variety you’re growing is at the upper limits of that temperature threshold. In that case, these kinds of things will be a big issue for those regions, like Burgundy, with strict laws about what can be legally planted.

WS: What can vintners do to adapt?

GJ: You have to really think about what wine regions are producing today. What did they used to produce, and how are they doing it differently?

Everybody started doing one viticultural thing: fine-tuning their vineyards, particularly with trellising systems. Everybody went from sprawl [letting the vine grow like a tree] to VSP [training vine shoots upward to form an umbrella-like hedge] structures. What happened to some degree is that we were fine-tuning the grapevine for the climate back then. And as the climate warmed, we’ve found that those tight VSP canopy structures were probably not the right thing to do. In the past ten years, I’ve seen VSP with cross arms on the top to get a larger canopy structure protecting fruit. Some people are even doing a true V, where the fruit zone is down at the bottom of the V. I’ve also seen other people do a situation where they have a straight VSP on the east side and a sprawl on the west side [to protect from greater late-day sun exposure and heat].

Those right there are simple adaptations and the kinds of measures people are doing. There are, of course, others. A great example is how we have historically planted on south-facing slopes because it gives you more solar radiation. But in a warmer world, planting on a north-facing slope may not be a bad idea.

Of course, one you often hear the most about in the media is that you have to change varieties. And yes, some people are doing it because the climate allows them to. Other people are doing it because they probably have to. I’ve heard more people planting Syrah, Gamay, even Tempranillo in the Willamette Valley because the climates are conducive to it now. We’ve arguably been about experimentation in the New World, trying to figure out what works where.

[Aerial view of vineyard plots at Abacela]

In Oregon's Umpqua Valley, which is warmer than the Pinot Noir–focused Willamette Valley, Abacela is able to grow Malbec, Spanish varieties such as Tempranillo and Graciano and varieties from southern France such as Grenache, Syrah and Tannat. (Andrea Johnson Photography)

WS: What is Abacela specifically doing?

GJ: I’ve taken over for my dad and am trying to be a little more conscious about our carbon footprint. We were one of the first wineries to do the Oregon Carbon Neutral Challenge. We have about 350 acres of other land in a conservancy, and we try to maintain that. We are looking harder at managing soil in terms of regenerative soils. We have a relationship with Wildlife Safari, where we provide hay grown in our open pasture land, and they provide “zoo doo” back to us. We take all our rachis [stems, leaves, etc.] and marc [stems, seeds, skins] from fermentations, and we blend that in with the “zoo doo” to make our compost. We’re trying very hard to make sure that we do those kinds of things to add back to the vineyard from the regional environment.

Also, I think all vineyards need to experiment to find out how things perform. We’ve gone from 27 different varieties down to 15 now. We feel pretty good about what we have, and we think that they’re very suitable to our climate today and likely will be for some time in the future.

WS: What are other climate-related concerns for vintners?

GJ: Precipitation. Dry summer environments are likely to become both warmer and drier, which is a challenge from a water standpoint. The West Coast will likely only become more dynamically driven to a broader, dry summer than we have today. Having the same amount of snow in the future is less likely too.

There are some places that I think have challenges with extremes. For example, look at Europe. For the past three or four years, late winter and early spring warmth have been producing bud breaks two to four or six weeks early. The problem with that is that cold events don’t go away. Frost still occurs, and some parts of Europe have been hit hard in the past few years.

Of course, varying levels of these kinds of things would probably also tie some of this into fires and smoke issues. In California, two years ago, a fairly large dry lightning event generated most of the fires in the West. … We will likely have a greater possibility for fires in the future just because there will be more fuels. And if more people are living in environments that are kind of fragile, to begin with, all it takes is one spark.

WS: Is there an optimistic takeaway for winemakers and wine lovers?

GJ: This industry is very dynamic. It has a lot of players that are very in tune. I think this is an opportunity for people to look at what they’re growing and how they’re growing and maybe do things that are different. In 20 to 30 years, we could have some absolute stellar wines coming from places we’ve never heard of before, or have different wines coming from places we have known for a long time but that create new notoriety.

There’s a lot of interest in the ability to adapt. I think the resiliency of the industry is very large, so I think the industry’s vulnerability will lessen over time. I’m very optimistic that there’s just a lot of individuals in this industry that will kind of float that for us—and, you know, I plan on being one of them.

Winemakers Are Poised to Lose Another Vital Tool to Climate Change

By Kathleen Willcox, Wine Enthusiast, February 15, 2022

Grapes are extremely malleable. Plant the same grape variety in different soils, alter the length of time they’re fermented or vessel they’re aged in, and the taste of the resulting wine will be vastly different.

But the climate grapes grow in, and temperature fluctuation from day to night called diurnal shift, have some of the biggest impacts on a wine’s quality. Just a few degrees’ difference can spell success or doom for sensitive varieties like Pinot Noir, which needs an average growing-season temperature of 57–61°F to thrive.

From frosts and heat domes, to wildfires, floods and droughts, climate change upends the wine industry in countless ways. But the more subtle effects of diurnal shifts are also important, if less frequently discussed.

“A lot of people aren’t putting two and two together when it comes to the diurnal shift,” says Greg Jones, climatologist and CEO of Umpqua Valley’s Abacela Winery. “There are multiple factors at work here. Many warmer regions are now ripening much earlier in the summer, and harvest is happening in August, when it used to happen in September or October. But cool nights are key to correct ripening, especially in September and October, and without that, the sugar, acid, flavor, aroma and phenolic characteristics of the grape will be thrown off.”

Recent climate change research confirms this. According to scientists at the University of Exeter, who looked at temperature patterns between 1983 and 2017, global warming is affecting daytime and nighttime conditions differently, with greater increases in nighttime temperatures being registered.

“Over the past century, nighttime temperatures increased by 1.5°F, while daytime temperatures increased 1.1°F,” says Jack Sillin, climate researcher at Cornell University. “That may not sound like a lot, but that’s a difference of 20%.”

Effect on Grapes

Winemakers depend on the diurnal shift to lock in flavor and brightness, especially in white grape varieties. Diurnal shifts can also impart higher tannins and more complete phenolic maturity, says Julio Sáenz, technical director at Spain’s La Rioja Alta.

“We don’t have exact data, but we have noticed a significant change,” says Sáenz. “Grapes are higher in sugar, lower in acid, there is delayed phenolic maturity and grapes are developing less intense and fresh aromas.”

Franco Bastias, agronomist at Domaine Bousquet in Mendoza, Argentina, notes that changes in diurnal shift are far from uniform.

“In the Uco Valley, the shift is still pretty nice, around 59–68°F, which helps us harvest grapes with remarkable natural acidity and a concentration of fruity flavors,” says Bastias. “But in the center and east of Mendoza, many growers are suffering, and the increase in night temperatures are producing grapes with less acidity and higher pH.”

Resolution in Field

Winegrowers are experimenting with a variety of short- and long-term fixes to contend with these challenges.

At Clos Mogadar, which has 100 acres under vine in Priorat and Montsant, Spain, Winemaker Rene Barbier Meyer says that the changing nighttime temperatures are pushing them to “abandon non-autochthonous varieties, especially the ones that have to be picked early. We’re replanting autochthonous varieties like Grenache and Carignan, and recovering old ones like Picapoll and Xarel-o,” for their lower alcohol levels and higher acidity. New vines are also being planted at higher elevations.

In Paso Robles, Daou Vineyard’s Winemaker Daniel Daou, who has 170 producing acres in Adelaida, says his vineyards are in a better position than most in the region because they’re planted as high as 2,200 feet above sea level and 14 miles from the ocean. Even so, Daou was alarmed enough by changes in the diurnal shift that in 2017 he developed a three-pronged approach to counter the effects.

“We use an organic product called BluVite to activate microorganisms in the soil and strengthen the vine’s ability to withstand thermal stress,” he says. “After a three-year trial, we noticed that it helped lower the temperature of the grapes between 3–5°F during heatwaves.”

Daou also uses shade cloth during the afternoon to shield grapes from sunburn. “It can make between a 5–7°F difference,” he says.

The third element is monitoring moisture in the generally dry-farmed vineyards. “During heatwaves, we water in microbursts, sometimes giving a half-gallon or so during heatwaves in August,” says Daou.

By reducing the impact of the extreme heat spikes on the grapes, Daou says he can maintain some of the freshness lower nighttime temperatures usually lock into place.

Resolution in the Cellar

According to Eric Glomski, founder and winemaker at Page Spring Cellars in Cornville, Arizona, when “the gap between day and night closes” at any of the 30 acres of vineyards he works with, he’s forced to change procedures in the cellar.

“The acid structure gets mucked up, and for our warmer sites, we have to acidulate the wines,” says Glomski. “Picking earlier isn’t always a solution for us, because we want the grapes to be phenologically mature.”

Glomski worries that Syrah, Arizona’s “trademark grape,” will soon no longer be viable because “the acid just can’t hold up to these changes.”

He’s already planting more high-acid grapes like Picpoul Blanc, Gamay, Barbera and Alicante Bouschet, anticipating their increased importance in blending as well as stand-alone bottlings.

In New York’s Finger Lakes region, Red Newt Cellars’ Winemaker Kelby Russell says that, in 2021, he “didn’t have a frost until Thanksgiving. We normally get our first frost in early to mid-October. We depend on those colder temperatures to relieve disease pressure and kill off pests like fruit flies.”

Delayed frost also impedes acid development and aromatic potential of their grapes. Short term, that means increasing spraying regimens in the vineyard, something Russell says he hates doing, and on rare occasions, “adding tartaric acid because the acid is so lacking. We added just enough so our Riesling could be correct for the region.”

In the long term, he says, “low acid can also lead to microbiological issues, which may mean we have to switch up our spontaneous fermentation. We are not looking for malo.”

To contend with the current state of climate change, growers may have to continue to cultivate higher-acid grape varieties, move plantings to higher ground and deploy a range of products in vineyards and cellars to ensure customers get the style of wines they’ve come to expect.

“The changes in the diurnal shift represent a pernicious problem,” says Jones. “There’s no easy solution or shortcut, unfortunately. We must reduce emissions drastically to prevent more warming.”

SOU professor says climate change impacts wine-making

A Southern Oregon University professor was interviewed on “60 Minutes” for a feature that aired this past Sunday about climate change’s impact on the wine industry.

A Southern Oregon University professor was interviewed on “60 Minutes” for a feature that aired this past Sunday about climate change’s impact on the wine industry.

Greg Jones, who specializes in the study of how climate change influences the growing and harvesting of wine grapes, sat down with veteran CBS reporter Lesley Stahl. He told her that grapes are “sensitive” to changes in Earth’s temperature and that it is accelerating the fruit’s ripening process — so much so growers are having to harvest them much earlier than normal.

The “60 Minutes” segment even noted that global warming is one of the reasons vineyards are migrating north of the renowned Napa Valley to places like Oregon, where it used to be too cold to grow grapes, according to Jones.

“The warming to date has helped the state's industry become more consistent and even world-renowned,” wrote Jones, who praised the legendary broadcast show, in an email to the Mail Tribune. “The problem is that additional warming and especially drying could challenge Oregon's wine production in the future.”

The “60 Minutes” segment named Willamette Valley as a region that’s become more popular for winemakers — but it did not mention Rogue Valley, which has its share of wineries and vineyards being impacted by climate change. Jones talked about this and his work at SOU in an interview a day after the “60 Minutes” segment ran.

This southern region of the state has been extensively studied by Jones, who taught and conducted research at SOU from 1997-2017. After leaving Ashland, Jones was named an “affiliate” faculty member — stepping away from the institution to pursue other endeavors, but not exactly retiring, either.

Jones — now CEO of Abacela Vineyards and Winery in Roseburg — has been named to numerous wine publications’ top 100 or 50 lists of influential people in the industry. He was also a contributing author to an international climate report that merited a Nobel Prize in 2008.

Over 20 years at SOU, Jones sought to better understand grape growing in the Rogue Valley, mapping all of the vineyards; collecting data on weather, soil and how the plants were growing.

In his latest “vintage report,” posted on his website www.climateofwine.com, Jones recorded 2021 as having the second warmest growing season on record.

“When you have drought occurrences and real intense heat, those two things, in combination, can be challenging to growing balanced fruit and wine,” Jones said. “I think the growers in the region have done a really good job managing and adapting to the conditions we have.”

Constance Thomas, manager at South Stage Cellars in Jacksonville, acknowledged climate change makes it difficult to grow grapes and produce wine.

“The climate change that’s happening has impacted the grapes all the way around,” Thomas said. “I know vineyard managers that have just left the business, partially because there are still extreme differences from year to year, it’s hard to get any consistency with their grapes.”

Echoing what Jones said on “60 Minutes,” Thomas confirmed in an email that South Stage Cellers has been picking its grapes “earlier and earlier each year.” She did not elaborate more on that before the newspaper’s deadline.

In an earlier phone interview, she talked about a variety of challenges South Stage faces, including the summer heat and how it impacts South Stage Cellars’ grapes.

“You need a certain length of time for the grapes to hang on the vine,” she said. “If the sugars get so high because the temperatures are so high, a lot of times, the flavors don’t get there.”

Thomas went on to say the impacts of climate change on her winery is not just related to heat.

“We are not getting the rain we normally get when we normally get it,” she said. “With climate change, there really is no normality at all.”

Last year, South Stage Cellars was supposed to plant another 50 acres of vines, but decided not to because of the predicted lack of precipitation.

“Winemakers have to be much more creative and try different things to combat climate change,” Thomas said.

The “60 Minutes” segment said wildfires have been known to impact vineyards — and not just if they’re completely burned down. Smoke can be a factor in harming the grapes.

Nevermind the Almeda fire of 2020, Thomas said her winery and others have felt the impacts of smoke emanating from wildfires not even near the Rogue Valley.

“Unless it’s a smokey varietal, it might have a different type of smoke – when varietals age, they might smell a little bit like bacon,” she said. “That’s not from wildfires.”

She acknowledged that dealing with an issue like climate change, that requires an all-hands-on-deck approach to mitigate, is tough — but winemakers are doing what they can.

“We have very talented winemakers in the valley and they’re doing a great job,” she said.

By Kevin Opsahl, Mail Tribune, Dec 27, 2021 06:59 PM

Greg Jones on MSNBC's The ReidOut with Tiffany Cross

[[TRANSCRIPT OF LIVE BROADCAST]]

TIFFANY CROSS, MSNBC HOST: Good evening, everybody. I`m Tiffany Cross in tonight for Joy Reid.

CROSS: All right, everybody. I know we have about 28 hours until the ball drops, but, in the words of Beyonce, we like to party. Sorry for my singing. I can`t.

But I do want to cheer to the new year. And I imagine, like me, many of you will be popping a bottle of bub with your friends and family tomorrow. Sadly, some of you will be drinking alone because you`re in quarantine or you have to be on air Saturday morning like me.

Whatever the reason, I`m sorry. But, even worse, some of you could be popping a bottle of English sparkling wine. I know, the horror. But that`s for an entirely different, but equally disturbing reason. Extreme weather conditions are starting to push good wine out of traditional regions like France, Italy and California into places further north and south, like Norway, Oregon and the aforementioned England.

It`s the literal polarization of wine. Take, for example, France. Extreme weather has hammered the country, leaving its world-class wine and champagne regions hurting. A French government forecasts showed that the 2021 harvest was the smallest in at least 50 years.

Now, that`s a devastating blow to a country whose second largest export industry is actually wine. The threatening effects of the climate crisis on wine are having serious and life-changing consequences.

I`m joined now by Greg Jones, CEO of Abacela Winery. He`s also an atmospheric scientist and vinicultural climatologist.

I hope I said that correctly. Greg, you will correct me if I didn`t.

[19:50:00]

This is a really entry interesting story. I mean, it`s obviously disappointing for champagne lovers, but the bigger challenge is, of course, protecting Earth.

What`s the solution to all of this? And because it`s so serious, I`m just going to take a sip of the champagne while you tell us what can be done to preserve our precious cocktails.

GREG JONES, CEO, ABACELA WINERY: Well, first of all, thanks for having me on air today.

This is a really big issue. We have been noticing in agriculture in general, but in grape growing specifically, climates have been changing all over the world, and the rise of extreme events that have become more and more problematic, whether it be heat extremes and/or hail and/or heavy rain, have really caused some major challenges.

In 2021, in champaign, a combination of frost, hail, heavy rain, and quite a bit of mildew led to a very, very difficult vintage. There will be some people that just will not even produce whatsoever. There`s hope, though. There`s still, I think, plenty of wine out there for this coming year.

Champagne does something that is very similar to what OPEC does with oil and what maple syrup is done within Quebec. They do have supplies that they keep behind for delivery for a year like this.

But the challenge is, is that the supply chain may be more difficult than anything.

CROSS: The supply chain is certainly a challenge with a lot of industries.

In hearing you talk about this, I`m curious. If we cannot address this challenge with champagne, like, what is the responsibility of the consumer? Like, will prices start to go up significantly? Should people be buying champagne, buying more champagne? I understand the champagne committee is trying to decrease the carbon footprint of what`s happening in these regions.

For us at home watching, like, what should we be doing?

JONES: Well, I think the whole industry is trying to look at this as a broader issue.

The idea, number one, is to really look at packaging. How does shipping glass bottles all around the world impact our carbon footprint? So I think there`s going to be some major changes in packaging in the future.

But, as consumers, we just need to be aware of where our products are coming from. Can we buy more locally? Or can we buy more sustainably in terms of how that product has gotten to our doorstep?

CROSS: Great advice, especially as so many people will be popping bottles tomorrow night for New Year`s.

Because tomorrow night is New Year`s Eve, I`m just curious what you will be drinking tomorrow night when it`s time to bring in the new year.

JONES: Well, I have to admit that I do you have an Oregon sparkling wine on my menu for tomorrow night.

I think there's some wonderful sparkling well wines made throughout wine regions in the United States. So, if you cannot, for whatever reason it is, find a champagne on the shelf at the marketplace, look for something else from maybe Upstate New York or Oregon or Washington.

There are some really good sparkling wines made by the producers out there.

CROSS: That`s really sound advice. And 2021 has been a challenging year. 2022 may be another challenging year. Please don`t take our wine and champagne away from us.

Thank you so much, Greg Jones. Cheers to you and happy new year.

And don`t go anywhere at home, because, up next, America`s youth poet laureate, Amanda Gorman, pens an extraordinary new poem to send us into the new year brimming with hope and inspiration.

We will be right back.

Greg Jones, CEO of @Abacela Winery and wine climatologist, on the impact of global warming on the regions in France that produce champagne, and wine making worldwide. #TheReidOut #reiders pic.twitter.com/7Gxrp8nDgD

— The ReidOut (@thereidout) December 31, 2021

Effects of climate change taking root in the wine industry

What are the signs of global warming? Glaciers are melting at an increasingly rapid pace. Persistent droughts are spreading. Well, we have another to tell you about – wine, as in what you probably cracked open for Christmas dinner.

Farmers who grow the grapes have seen the effects of climate change in the soil, in the roots of the vines, and the yields of their crops.

France, a major center of winemaking for centuries, is experiencing increasingly higher temperatures and extreme weather conditions that have damaged vintages, and livelihoods; this year was particularly dramatic.

France recorded its smallest harvest since 1957 and stands to lose more than $2 billion in sales - a huge blow to the country's second largest export industry.

And it's hitting nearly all the winegrowing regions where they make dry whites, fruity reds and fizzy champagne.

All bubblies are called sparkling wine. But champagne is made here and nowhere else –

in these vineyards and villages of Champagne located in northeastern France. There's a mystique to champagne, an aura of romance. Coco Chanel once said, "I only drink champagne on two occasions, when I am in love and when I am not." They've been producing this "wine of kings" here for centuries.

Lesley Stahl: So how long has this winemaking business and the vineyards been in your family?

Christine Sevillano: From 1700.

Lesley Stahl: 1700.

Christine Sevillano: Yes.

Christine Sevillano took over the family business and its 20 acres of vines 14 years ago. She's the 10th generation.

Christine Sevillano: This is the cellar of my grandfather.

Lesley Stahl: Oh.

After surviving the French Revolution and two world wars, her family's house of Piot-Sevillano faced its worst year ever in 2021.

Christine Sevillano: We lost 90% of our harvest.

Lesley Stahl: 90%?

Christine Sevillano: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: How many bottles were you able to produce this year as opposed to a normal year?

Christine Sevillano: A normal year, I produce around 40, 50,000 bottles.

Lesley Stahl: And this year?

Christine Sevillano: Zero. It's the first time in the history of my winery that we will not make champagne.

Lesley Stahl: Not a single bottle from this winery?

Christine Sevillano: Yes.

Higher temperatures and extreme weather episodes devastated not only her harvest but much of Champagne's.

Christine Sevillano: It rained in two or three days that it rained normally in one month. Even my father told me that in his career he has never seen that.

Lesley Stahl: Almost flood like?

Christine Sevillano: Yes.

The worst of it, she says, came in June and July when the heat and the rains resulted in a more crippling outbreak than usual of funguses like mildew contamination.

Christine Sevillano: In fact, when the grapes are contaminated, the-- the fruit is drying and after we can't use it because there is no juice, nothing.

Lesley Stahl: And you attribute this to climate change?

Christine Sevillano: Yes, because it was so extreme. It's not normal.

This year's extreme weather not only battered Champagne and the foundation of its economy, but nearly every one of the wine-producing regions in France -- Burgundy to Bordeaux, where some of the highest quality, best-known and best-tasting reds and whites are made.

Lesley Stahl: And these are what grape? What what--

Jacques Lurton: This is merlot.

Lesley Stahl: I love merlot.

Jacques Lurton: Yeah, merlot makes a beautiful, soft-rounded wines.

Jacques Lurton, the head of a wine family dynasty, runs the Château La Louvière and several other wineries in Bordeaux. He says vine disease is getting worse all over France because of the rising temperatures.

Jacques Lurton: We don't have winters anymore, almost. In wintertime, normally you get colder conditions. These cool conditions tend to kill the funguses or the disease. So normally, winter cleans the situation, you see? But the most important problem that we have is what we call spring frost.

Spring frost was so severe in April this year that winegrowers were on their knees lighting bales of hay and candles between their vines in a mostly futile attempt to protect their young buds.

Jacques Lurton: It is the largest catastrophe we have ever suffered. Because before we had some spring frost in some regions, but this is the first time we have it all over France. Now, due to the fact that we don't have these very strong winters, the buds start to open and then expose themself to this series of spring frost that we have.

Lesley Stahl: And that is the crux--

Jacques Lurton: And that, you see, is what affect the most the quantity of the grapes.